What comes after the rain

"After Rain" is the title of the second Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, which runs from 19 February to 24 May in the Riyadh suburb of Diriyah. The rise of the House of Saud began in Diriyah in the eighteenth century. It was here that the family allied itself with the Islamic scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the founder of the puritanical, strictly religious Wahhabism.

This is what makes Diriyah such an interesting choice as the country's launchpad into a cosmopolitan open-mindedness. The driving force here is the much-cited Agenda 2030 initiated by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

While Germany's neoliberal public debt limit has put cultural life in Germany in an artificial coma, Saudi Arabia's Agenda 2030 has allowed a deluge of investment to water the country. The impact has been astonishing; Saudi Arabia is being swept up in a wave of positive thinking.

The biennale is the ideal testing ground for all this: it is open to the public, while at the same time being exclusive and elitist. It is global yet local, progressive yet not revolutionary. Selecting the issue of water and the environment as the biennale's dominant theme was a clever move: it is now the only common denominator in the global community.

A second theme – albeit an unspoken one – runs through the exhibition too: female self-assertion. The well-known German curator Ute Meta Bauer is the artistic director of the biennale. Its CEO, Aya Al-Bakree, is also a woman, as are about half of the artists invited to exhibit in Diriyah. If the biennale is taken as a yardstick, then women in Saudi Arabia are not oppressed, but supported and promoted to a greater degree than women in Germany at the present time.

The Biennale's German curator

Ute Meta Bauer and her four co-curators have put together a highly aesthetic show of global contemporary art, the appeal of which is only enhanced by the unusual surroundings. Diriyah is home to the renovated former residence of the Saudis, an old Arab clay-building settlement, the World Heritage Site of the At-Turaif District. From the exhibition halls of the biennale, visitors can see the river bed of the Wadi Hanifa, which is used as a road in the dry season.

The outdoor part of the exhibition, which is bathed in harsh sunlight, has no less than two highlights. The first, a pergola made out of textiles by Azra Aksamija (b. Bosnia, 1976), turns the path leading along the exhibition halls into a play of light and shadow that makes walking back and forth between the halls a pleasure rather than a trial.

The second is by young Mohammed Alfaradj (b. Saudi Arabia, 1993), who has decorated the transition to the viewing platform over the wadi with imaginative sculptures made of dried palm fronds and other materials taken from palm trees. Are these skeletons? Primeval beasts? The fossils of some mysterious plant? Or simply a desert ikebana?

Although one could stand here contemplating at length, the threat of sunburn is never far away in Riyadh – even in February – and the pavilions beckon. As an extraterritorial area with no reference to the dominant environmental theme of the biennale, the first of these pavilions presents the weakest link to the exhibition.

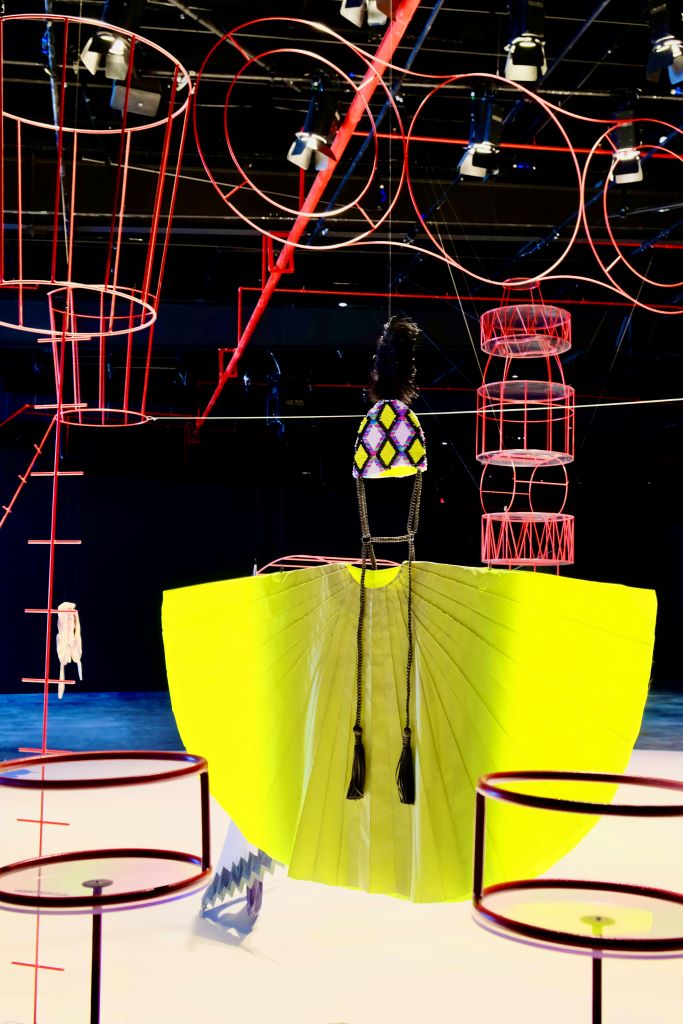

Nevertheless, the colossal, filigree abstraction of a circus ring entitled "Charivari" by Dubai-based Taus Makhacheva (b. Moscow, 1983), is pleasing. It is reminiscent of the state circus in Baku, but also – as we are told by the accompanying text – of the performative, playful and ironic character of art.

Water and living

It is only the second hall that really plunges the visitor into the theme of the biennale. The most powerful exhibits are not, however, those installations that reflect the issue of water with their cool greenhouse and laboratory aesthetic – such as the OrtaWater cleaning station made out of recycled material by Lucy + Jorge Orta – but several photo series.

One of these is by Bahrain-based Camille Zakharia (b. Lebanon, 1962). In the improvised huts of Bahraini fishermen, which Zakharia has captured in his photos, the boundary between inside and out is blurred. It is almost as if the photographs are not actually the work of art, but the tree-house-like fantastical huts made out of bulky waste that are built on water and can only be reached by footbridges.

The new buildings and single-family homes in Riyadh that have been built between the cut-away rocks of the city and captured in photos by Zakharia are just as astonishing. "The Mountain My Neighbour" is the title of a series of photos specially commissioned by the biennale that illustrates in a meaningful way both how nature and culture exist side by side and the reciprocal displacement of and competition between the two.

Forgotten artists

The next hall focuses on the internationally overlooked recent history of art in the Near and Middle East. The prominent presence of female artists was undoubtedly a conscious decision on the part of the biennale's curators – and it is a good one.

Although these female artists from the Near and Middle East have hardly ever been able to work without resistance and restrictions, they have created some outstanding works. Nevertheless, few receive international recognition during their lifetime.

The works of Lala Rukh (1948–2017) from Pakistan are particularly impressive. Shortly before her death in 2017, she was invited to exhibit at Documenta 14 and passed away while it was running. Her "works on paper" are abstract, in some cases virtually indiscernible strokes of the pencil, figurative suggestions of the female body.

This is art at the edge of silence – or rather invisibility. It is an artistic, aesthetic counterpart to the artist's political activities: Rukh printed banned writings of the Pakistani women's movement in secret.

Journey to al-Ula

Saudi Arabia used to be more isolated than North Korea. Now the country is presenting its friendly face to the world and wooing Western tourists. Text by Karin A. Wenger, photos by Philipp Breu

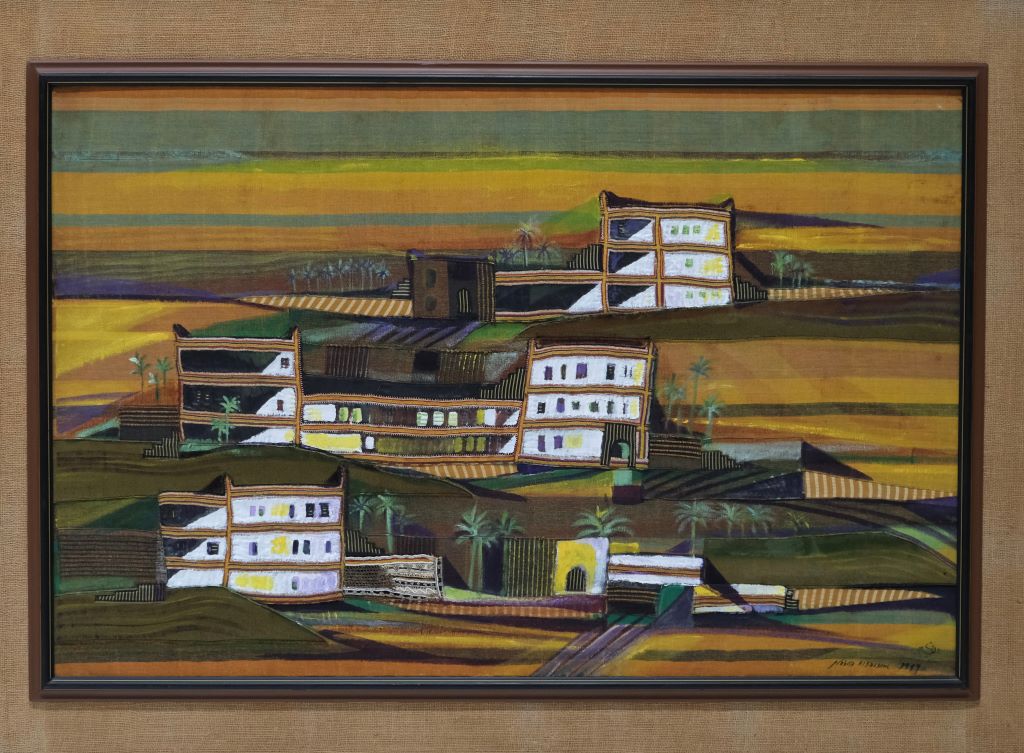

The works of established Saudi artists also have their charm. In the work of Nabila Al Bassam, for example, we see structures and landscapes that are typical of Saudi Arabia on a patchwork of textiles, the effect of which is reminiscent of the Tunisia-inspired works of August Macke and Paul Klee.

They are suspended somewhere between abstraction and naive art and are, in this way, the perfect mirror for the possibilities and limitations of the creativity of Saudi women before the most recent opening of society.

Naturally, the naivety is in itself also a skilful, intentional effect: like many others, Al Bassam studied in Beirut and the United States. With their artistic cosmopolitanism, the older artists in the Near East have paved the way for the younger generation, for whom studying abroad has become a matter of course. They are among the most determined supporters of societal change.

Works of art by younger female artists

The next two halls are devoted primarily to such younger female artists. Swathed in inky black – just like Saudi women until recently – these halls feature lighting that perfectly showcases the individual artworks. With lighting such as this, almost everything becomes a work of art, and none more so than the work of Dala Nasser (b. Beirut, 1990) entitled "Mineral Lick", a large, robe-like sheet that is suspended from the ceiling and shimmers in shades of rust and yellowish green.

The colours are the result of water pollution from old pipes. Beautiful yet simultaneously threatening, the poisoned tongue surges towards the beholders, threatening to devour them whole. The sheer aesthetic of pollution highlighted by Dala Nasser is both simultaneously disturbing and reminiscent of the large-format photos of polluted landscapes by Edward Burtynsky.

In sharp contrast to "Mineral Lick" – like a yearning for purity – are the hundreds of bars of Arab soap that Sara Abdu (b. Jeddah, 1993) has arranged, brick-like, one on top of the other to form towers, creating a light installation with luminous soap-bar shaped patches on the floor. "Now that I have lost you in my dreams, where do we meet?" is the title of this work.

The Arab culture of bathing and the tradition of washing the dead, the scent of the olive oil soap and the experience of loss hinted at in the title are all captured in this sculpture, which is as fragile as it is powerful, as heavenly as it is eerie.

Politics barely present at all

One of the most agreeable aspects of the biennale is the fact that politics barely raises its head at all. The reason for this is, of course, that all too political art is unwelcome in Saudi Arabia. But when it comes to controversial issues, this is now also the case in Germany; the only difference being that in Germany – unlike in Riyadh – no one wants to admit it.

Because the exhibition was planned long before the 7 October 2023 and Hamas' surprise attacks on Israel, not even the war in Gaza plays a role here. In any case, this does not give rise to much controversy here in Saudi Arabia. The view of the situation is unbiased, which means that the barbarism is recognised and identified as such.

Anyone weary of looking at things in darkened rooms can take a break at Senegalese cook Youssou Diop's Njokobok bar overlooking the wadi. The intense juices and teas on offer, which are laced with mint, ginger, rose hip, basil and turmeric, are a wonderful alternative to the alcohol that is prohibited here. While sitting on bar stools, sipping their juices, visitors strike up conversations about things like the equivocal nature of the biennale's title.

In the desert, after the rain comes the flowering season, and on the surface, this is ostensibly what "After Rain" means. But upon further reflection, the title of course also hints at the environmental apocalypse, just like in the most famous poem in pre-Islamic Arabic literature, the "Mu'allaqat" by Imru al-Qais (sixth century).

The last lines of the poem read as follows:

"The clouds poured forth their gift on the desert of Ghabeet, till it blossomed

As though a Yemani merchant were spreading out all the rich clothes from his trunks,

As though the little birds of the valley of Jiwaa awakened in the morning

And burst forth in song after a morning draught of old, pure, spiced wine.

As though all the wild beasts had been covered with sand and mud, like the onion's root-bulbs.

They were drowned and lost in the depths of the desert at evening."

Blossoms can come after the rain. But so too – as in this old Arabic poem – can the deluge.

© Qantara.de 2024

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan