When the water buffalo die

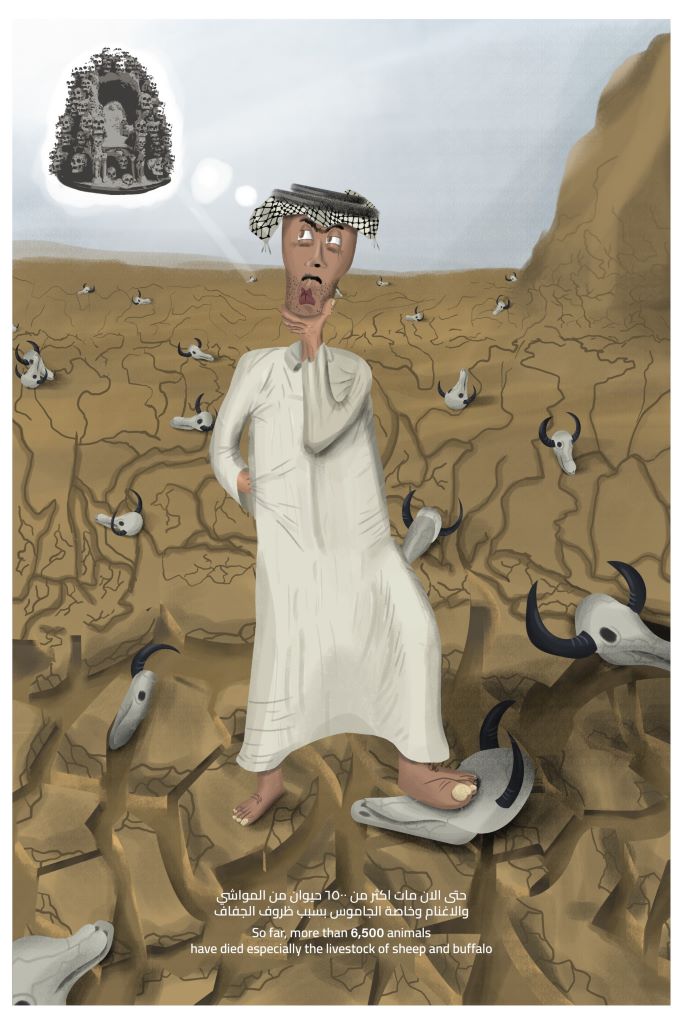

"When water buffalo no longer have enough water, they die, then their eyes go red and they can't survive any longer." Hussam Qais Taha rows the narrow boat through the marshland reedbeds and points to a dead buffalo floating on the water. He can't say precisely how many animals have already died: "But it's in the hundreds." If water levels in the marshes of southern Iraq – a UNESCO world heritage site – carry on sinking, before long there'll be no animals left, he says.

Water buffalo need to cool their coats in the water to withstand the heat. If there's no longer enough water for them to do that, this leads to the spread of bacteria and viruses. The animals go blind, get sick and die. If the king of the marshes goes, a creature that's lived here since time immemorial, in the place thought to have been the location of the Biblical Garden of Eden, others will also die.

"Even now," says Hussam, "there are only two species of fish in the marshes, whereas there used to be five." Taha is a Marsh Arab, as the local people who live here are known. He's 23 years old, has a wife and daughter, studies chemistry at the University of Basra and has made it his mission to save the marshes that provide a habitat for him and another 10,000 people in the Shafi region in northeastern Basra, Iraq's second largest city. But that homeland is under threat like never before.

Every summer more areas dry out

A family needs around 10 water buffalo to guarantee a livelihood. The buffalo milk is turned into yoghurt, cheese and "Gemar", the legendary cream that's eaten for breakfast in Iraq, spread on fresh bread with honey.

Um Haider has found an effective way to market the products. With money from the European Union, she's set up a store for buffalo products on the main road to Basra. Business is flourishing. Anyone visiting the marshes or travelling to the neighbouring province of Maisan shops at Um Haider's store. But if water levels continue to decline, Um Haider won't survive either.

"With every summer," explains Hussam, "more areas evaporate and dry out." Last year, the thermometer read over 50 degrees for weeks – in the shade, he adds. But there's barely any shade in the marshes. The wetlands once stretched as far as Um Haider's store, but now the waters only begin eight kilometres beyond that. And even there, it's no longer an unbroken body of water.

Dangerous salinisation

The marshlands extend over an area of 211,544 hectares and are a wetland ecosystem in an extremely arid and hot environment. They are almost totally reliant on water inflow from elsewhere, which leads to marked fluctuations in water levels throughout the year.

The western Ahwar – Arabic for marshland – around the city of Nasiriya is fed by the Euphrates, while the marshes in the east around Basra receive water from the Tigris.

Water scarcity in both rivers and rapid evaporation caused by the increasing heat go hand in hand with increased salinisation exacerbated in the past by human interventions. But water shortages in the Euphrates and Tigris are also due to dam construction in the rivers' upper reaches, in Turkey and tributaries in Iran.

Professor Sajid Saad Hasan says the 'salt line' has shifted around 100 kilometres inland over the past 20 years, since the Americans and the British invaded Iraq.

The director of the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Basra uses the term 'salt line' to refer to the threshold where the water's salt content no longer allows the existence of any life. This now runs through Abu al Khaseeb, just under 25 kilometres to the south of Basra, he says.

Studies carried out by his faculty have shown that the water's salt content of 1.1 percent before 2003 is now between nine and 24 percent.

Even the date palms are dying

The UN organisation WFP has ascertained that nine billion cubic metres of groundwater in the region are salinised. This would suffocate all plant life, says the professor. Farming is no longer possible. This although the province of Basra was nationally famous for its tomatoes and supplied all of Iraq with the tasty, aromatic red vegetable. Now everything comes from Iran, says Sajid, "nothing grows here anymore".

That's due to the Shatt al-Arab, the confluence of the Euphrates and the Tigris, which is carrying less and less water, he adds. There's no longer enough freshwater in this river to push back the salt water of the sea. The result: salinised water and salinised soil. "Not even the date palms can stand it, although they're considered robust. They're dying too," says Sajid.

Although Iraq signed up to the Paris Climate Accords in 2020, which means it must do everything in its power to avoid greenhouse gases and rising temperatures, no significant steps have been taken so far. The country did manage to put up a prestigious pavilion at the UN Climate Summit Cop 28 in December in Dubai; and shortly before the event, the prime minister announced the start of a nationwide campaign to plant millions of trees.

Contaminated groundwater

But that's all the government is doing. The gas produced by oil extraction is still being emitted into the air, the few trees that remain in cities are being chopped down to create residential areas for those quitting rural regions and agriculture doesn't stand a chance against the powerful oil lobby.

"I've got the smallest budget of the entire university," says Professor Sajid. "Only 14 students will graduate from my department." The business faculty has 4,000.

Alaa Bedran sits slumped on his chair in the department for the environment at the provincial administration in Basra. Since demonstrators set fire to the provincial council building in 2018, venting their anger at idle government officials, corrupt deputies and ideology-driven Islamist parties, Bedran has had to make do with a container provisionally located in front of the port authority building.

The head of the environmental department disagrees with the idea that the groundwater is contaminated. "Contamination? No," he says, "it's always been that like that." What the official does concede is that 70 percent of agricultural land is currently begin used by oil companies developing and expanding new oil fields and that this is a rising trend. But Bedran doesn't give the impression that anything will ever be done to change this.

Iraq: thousands of dead fish wash up amid on-going drought

Nevertheless, professor of agriculture Sajid in Basra and Hussam in the marshes are pleased that the issue of climate change caused by oil production was at least on the agenda at the Dubai environmental conference.

It was the first time the matter had been addressed since climate conferences like this began. Both agree that the future challenge for the entire region is to work out how saving the climate can be aligned with economic interests.

This is because like other Gulf states, Iraq's state budget is mainly financed by oil sales – more than 90 percent in the case of this particular nation. Other income is marginal. Hussam indicates the spot next to his buffalo shelter: "Rumaila, the world's largest oilfield, extends up to that point," he said. If drilling were to start here, then the animals would have to leave. "If there are any water buffalo left at all by then."

© Qantara.de 2024

Translated from the German by Nina Coon